The song of Notre-Dame

“Three hundred and forty–eight years, six months, and nineteen days ago to–day, the Parisians awoke to the sound of all the bells in the triple circuit of the city, the university, and the town ringing a full peal.” —Victor Hugo, Notre-Dame de Paris, 1831

We all know the tale, whether we’ve seen the dark yet sweet Disney adaptation or have read Victor Hugo’s original text. It’s the tale of a deformed and deaf bellringer named Quasimodo, his beloved gypsy dancer Esmeralda, and his feared guardian, archdeacon Claude Frollo. One of the most sought-out neighborhoods in all of Paris is the 4th arrondissement: home to the famed English bookstore, Shakespeare and Co., the bouquinistes stationed along the Seine, and most importantly, the greatest religious behemoth to grace the Parisian skylines, Notre-Dame.

Today, the scene looks slightly different from Quasimodo’s times. Tourists extend selfie sticks at absurd angles to get in all the majesty of the church behind them. At night, ill-behaved kids spatter the church’s facade in green lights from laser pointers. But sometimes, when I see women dancing with fire and hula hoops, that remind me of Esmeralda.

The folklore of Hugo’s story extends to the surrounding businesses. Café Esmeralda, for example, is a great place to get a café viennois. The nearby cobbled streets pay a minute homage to the cathedral’s medieval roots, suggesting that they’re not completely overrun by modern life. One can almost imagine what it must have been like that January 6th, 1482, surveying from atop a land as mystifying as it was exhilarating.

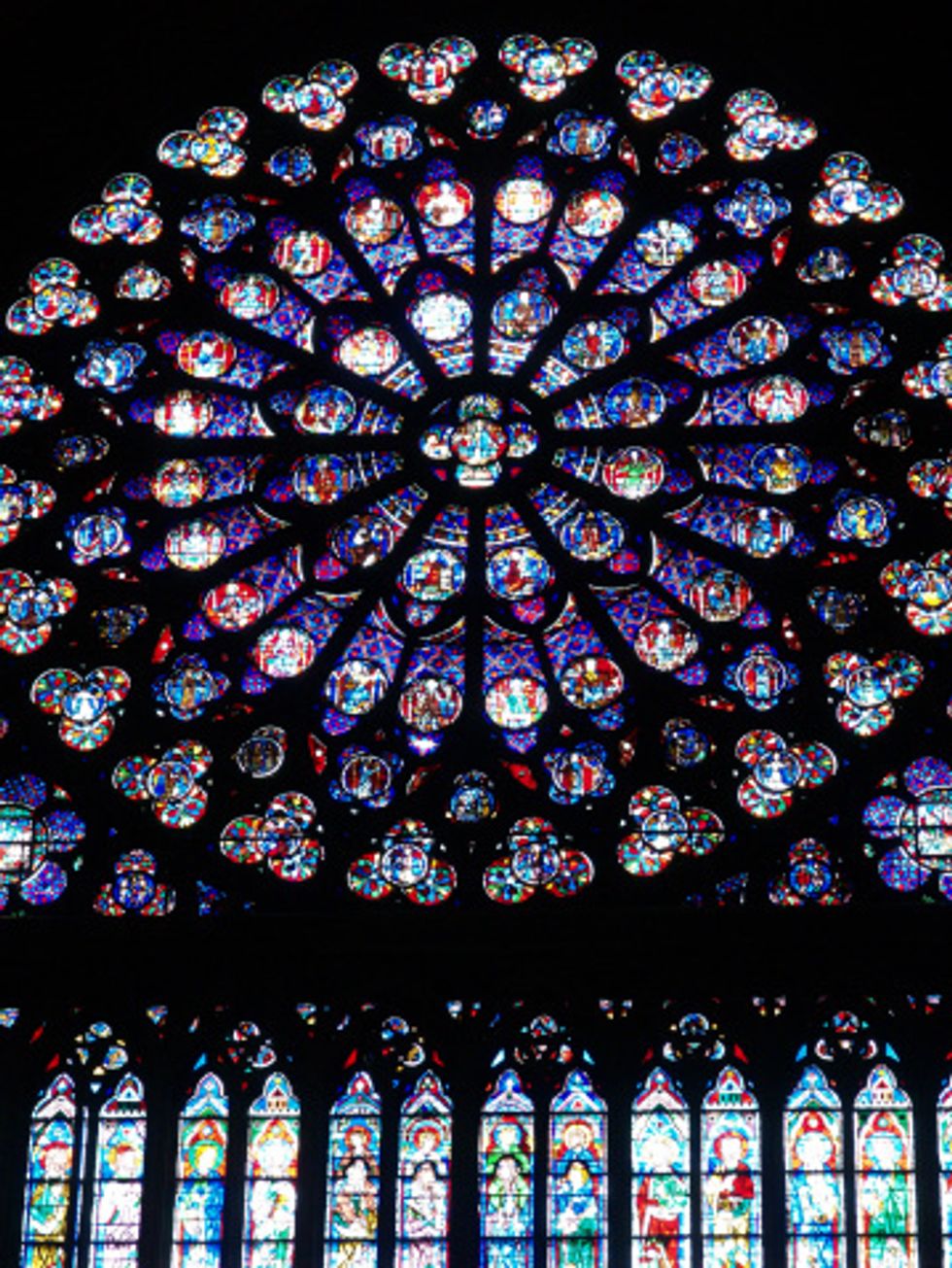

The construction of Notre-Dame, a project meant to accommodate the expanding Paris population, began in 1163 and wasn’t completed until 1345. But when you see the grandeur of the building, with its façades, rose windows, and flying buttresses, you can get a sense of just how massive this undertaking would be. But tragically, during the French Revolution, the statues and treasures were destroyed and plundered, all except for the massive bells. Hugo, a great advocate for historical preservation, recognized the artistic value in the cathedral and wrote Notre-Dame de Paris as a love letter to antiquity. But it wasn’t until after Hugo published his book that architect Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc began restoration of the cathedral in 1844. It was a reconstruction that would be more than just physical, but spiritual.

The Notre-Dame that we know today has 387 steps, 28 statues depicting the monarchs of Judea and Israel, 3 rose windows, and a 13-ton bell. And who could forget those gargoyles? If you’re looking for a relic of French history, look no further than Notre-Dame de Paris.