The Politics of Female Sexuality in French Cinema

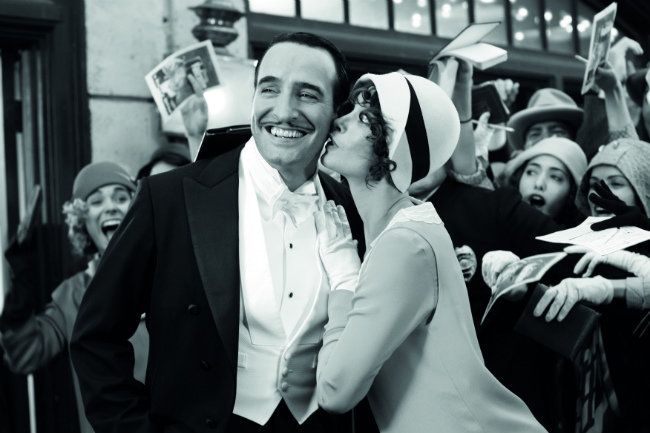

Courtesy of Breathless (1960)

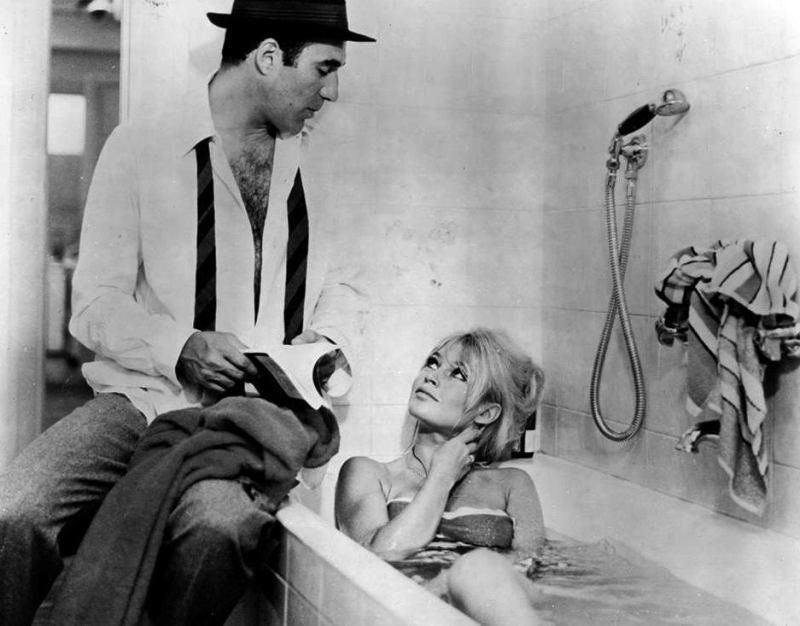

Photo by Walter Daran/The LIFE Images Collection

When I first started to appreciate film, I was a freshman in college who ventured into film studies after buying the Criterion Collection release of Jean Luc Godard’s Breathless (1960) in an empty Barnes and Noble. I bought the film because I had several unused gift cards, and because I thought the sleeve of the DVD seemed artistic and cool in an unapproachable way, and that my buying it would signal my own unapproachable, artistic vibes I was fumbling with at the time.

Watching the film proved to be a similar experience, a type of “Oh…I get why it’s groundbreaking” admiration coupled with my envy for the sheer style, albeit the anarchist philosophy of the story and characters. I had discovered European cinema, the French New Wave and all of its cigarettes, Anna Karina, tracking shots, and later, as my budding film studies progressed, Italian Neorealism.

I’ll spare you my journey with Godard because my enchantment with European movies seemed strongest with female directors, the women who are now grouped in with the men of the French New Wave, the women who were there the entire time, writing and directing films about women. Agnes Varda’s Cleo from 5 to 7 (1962) is cited as a hallmark movie of the movement, but I suppose her addition to the male club is more of a glaring reminder of the directorial gender gap in the sixties onward. Cleo from 5 to 7 is about, in brief, a beautiful woman coming to terms with her expiration date, courtesy of a cancer diagnosis. Her existential crisis is a commentary on how women are told again and again that our bodies are the basis from which we are given value, power, and in Cleo’s case, life. I always found the movie to be a poetic note for all women that our time is limited, but not measured by the elasticity of our flesh.

I remember the lethargy I felt watching Chantal Akerman’s Je, Tu, Il, Elle (1974), a film that features a mattress, a woman, and not much else. In the moments when Akerman leaves the camera static, the film exudes the energy of the young filmmaker exploring her own promiscuity and nuanced behavior. In retrospect, I think these films taught me how to write about feminism through the context of visual narratives, but I also realize—and certainly appreciate—that these films attempted to find power in characters who were aloof, or passive to their own budding agency. These directors were exploring the reality of the female body as a complex and unflinching force, and the intensity of discovering one’s agency in a world eager to categorize, sexualize, and police that agency.

It’s hard to depict what a feminine power looks like when so much of cinema has been made by men for men, with women accessorizing the narratives and screens. Éléonore Pourriat’s The Oppressed Majority (2010) attempts to subvert this familiar patriarchy by imagining a society in which men are cat-called, objectified, and harassed while walking down the street. It’s a sharp, satirical enactment of the woman experience, with men starring as the leading ladies. It’s not as simple as saying these directors celebrate womanhood or femininity (as so many superficial American films do); often, it’s the inverse, with characters who are anxiety-ridden to extent of animalistic neurosis.

What are celebrated in these films is the need to want, the need to desire, and how indulging this selfishness is innately human. In order to want, something, or someone, or someplace has to become an object of affection (even obsession); and herein lies the violence—the female gaze, which has every close-up, panning shot, and sex scene of the male counterpart. I’m not sure there are enough American, female filmmakers who know how to depict the gaze of a woman without also enforcing the tropes used in familiar rom-coms and female-driven comedies. Not everyone is an exhausted mother of two, hungry for the perfect marriage and kitchen backsplash, prompted by their girlfriend to let loose for the weekend. French directors know how to depict the female gaze, and it’s more visceral and powerful than Carrie Bradshaw looking for love in Manolos. Women in French cinema are sexual, and yet, their sexuality isn’t marked by the outward expressions of their desire; instead, by the intellectual—sometimes physical—consequences of their conquests.

Feminine power, I’ve realized, is a woman at her most vulnerable, emotionally naked in front of the screen. The erotic fascination with the female body in Julia Ducournau’s Raw (2017) is anything but glamorized, and still, it evokes a feminine rage that could be interpreted as a battle cry. What’s depicted is a young woman’s carnal craving for human flesh—a visceral metaphor for Justine’s (played by Garance Marillier) sexual awakening. Flesh and meat bits aside, Justine’s monstrous transformation is a visual depiction of her inability to rationalize her desires. Justine acknowledges—like every human—that she is a part of a system, particularly the one of her body (made of bones, muscles, and organs that’s susceptible to everything, including lust).

Raw is hard to watch—and the blood and finger eating has a lot to do with that—but even harder to metabolize for its unflinching examination of how our bodies undergo (sometimes irrational) transformations, even mutations as a symptom of being human. Ducournau’s film reimagines body horror in a feminist context; all the blood, aches, pains, and screams of the female body are simply the pangs of womanhood. And all the fleshy love bites are collateral for playing with the desires of the body. This isn’t my attempt to add to the somewhat comical mystique of the French woman, whose parenting, style, skincare routine, and diet reign supreme to her sisters in the West; but, it is my commentary on setting new standards for feminist filmmakers in the States. Why start with the pretty frills of our narratives when the ugly frills are so much more compelling, so much sexier?

- black and white

- female directors

- feminism

- film noir

- film reviews

- francois truffaut

- french cinema

- french film

- french language

- french movies

- french new wave

- interest in sex

- isabelle huppert

- jacques rivette

- jean luc godard

- la vie

- movie of all time

- movies

- olivier assayas

- sexual activity

- sexual desire

- sexual dysfunction

- the politics of female sexuality in french cinema

- women sexual

- young woman